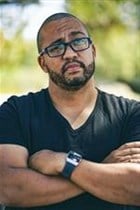

The Presidential Climate Commission (PCC) has laid out a bold strategy to accelerate South Africa's transition to renewable energy, speaking about the urgent need to align the country’s energy policies with international climate commitments. PCC executive director Dr Crispian Olver, speaking at the thirteenth annual Windaba, highlighted the challenges and opportunities facing the sector and called for a rapid scale-up of renewable power projects.

Olver reminded the audience that while South Africa has commendable climate and energy policies, the real struggle lies in bridging the gap between policy and practical implementation.

“We've got some very good, very progressive policies on energy and on climate,” he said. “The gap between policy on the one hand and implementation is the big issue.”

This gap is felt acutely in sectors like wind energy, where technical and financial constraints frequently hamper progress.

The PCC’s strategy includes ambitious targets for renewable energy deployment, aiming for 50 to 60GW of renewable power over the next decade – which averages out to between six and 8GW of new capacity annually.

“We were advocating what the government seems to have now finally come around to, which is an exponential acceleration in the rate of deployment,” Olver explained.

Global trade

This aggressive buildout is crucial if the country is to meet its emissions reduction targets and maintain global trade competitiveness, especially given the new international policies like the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

Olver highlighted the economic imperative of decarbonisation, warning that failing to transition the country’s power sector could result in severe penalties in global trade.

“The world’s global trading machine is changing very rapidly, and you have to think very seriously about the emissions intensity of the products being produced, and how they will compete in a very different global trading environment,” he said.

The implications are clear: South Africa’s energy-intensive products, if not decarbonised, could face export barriers that would stunt economic growth.

Grid concerns

Another cornerstone of the strategy is the overhaul of the power grid to accommodate a renewable-dominant system.

The PCC estimates that over 14,000km of new transmission lines need to be built to support the projected growth in wind and solar power.

Oddly, Olver advocates for a robust mix of battery storage, pump storage, and even gas turbines is essential to balance the grid.

“The critical things we need are colocated battery storage, peaking support we need a chunk of probably gas-fired peaking power to balance the grid,” said Olver.

One of the key recommendations is a fundamental reform of electricity pricing to create a fairer and more sustainable financial model for the sector.

Cost reality

Current pricing mechanisms, according to Olver, are not fit for purpose and fail to reflect the real costs of generation and supply.

“At the moment we do not have cost-reflective tariffs that allow a flow of finance back to [the grid operator],” he explained.

We need pricing reform that properly disaggregates fixed and measurable costs.

The PCC is advocating for two distinct models for grid expansion: a state-backed core grid managed by a central entity and a secondary system driven by IPPs.

Olver believes that an IPP-backed model will better handle the complexities of the renewable energy buildout, allowing for more agile responses to investment and capacity needs.

’Go big or go home’

Addressing the role of the wind industry, Olver urged stakeholders to step up and play a bigger role in the national energy transition.

“Go big or go home. You’re positioned to play a much larger role in the power generation system in this country, which means you need to invest a lot more in some of the broader contexts that enable you to be that driver,” he asserted.

This includes localising manufacturing to reduce dependency on imports and actively participating in skills development and community empowerment initiatives as part of the just transition.

Olver’s calls on the renewable energy sector to seize the moment and deepen its engagement with the government to turn the country’s renewable energy potential into reality is clear: “You’ve seen government wanting to be a partner to the industry, and I would seize that opportunity with both hands.”