Leanne Manas is a familiar face on South African television. Towards the end of 2023, the morning news presenter’s face showed up somewhere else: in bogus news stories and fake advertisements in which “she” appeared to promote various products or get-rich-quick schemes.

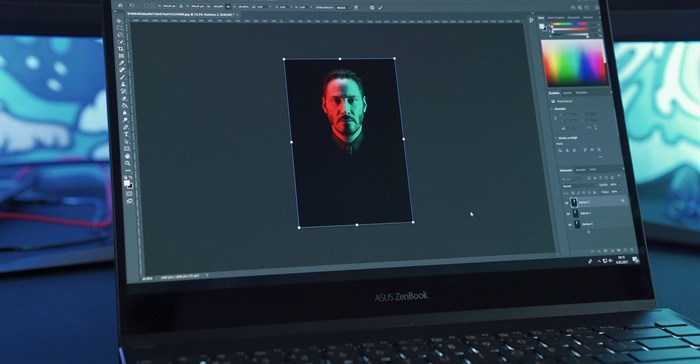

It quickly emerged that Manas had fallen victim to “deepfaking”. Deepfakes involve the use of artificial intelligence tools to manipulate images, video and audio. And it doesn’t require cutting-edge technical know-how. Software like FaceSwap and ZaoApp, which can be downloaded for free, mean that anybody can create deepfakes.

Deepfakes were initially used in the entertainment industry. For example, an actress in France, who was unable to film her parts in person for a soap opera due to Covid restrictions, still played the role thanks to deepfakes. In the health industry, deep-learning algorithms, which are responsible for deepfakes, are used to detect tumours through pattern-matching in images.

But these positive applications are few and far between. There are rising global concerns about the effect deepfakes might have on democratic elections. Recent reports suggest that deepfakes are on the rise in South Africa and that South Africans seemingly struggle to spot them.

It is worrying, then, that South Africa’s government hasn’t yet taken any legislative steps to combat deepfakes – especially with the country’s national elections scheduled for later this year. I am a legal scholar specialising in sport law, with a particular focus on image rights. I’m especially interested in the recognition of an individual’s image right and the legal position when their likeness is misappropriated without their consent. That includes the use of deepfakes.

In my LLD thesis, I argued that a person’s image needs clear legal protection, taking into account the realities of digital media and the fact that many individuals such as influencers, athletes and celebrities generate an income from commodifying their image online. Promulgating legislation will create legal certainty in South Africa as it pertains to an individual’s image.

International examples

Various states in the US have already taken action to deal with deepfakes, mostly in the context of elections. For example, Texas became one of the first states to criminalise the use of deepfakes, especially if the content of the deepfake relates to political elections. It also recently passed a second bill which targets sexually explicit deepfakes. So it’s a criminal offence to create a deepfake video with the intention of injuring a political candidate or influencing an election result, or to distribute sexually explicit deepfakes without the consent of the individual, with the intention to embarrass them.

Maryland and Massachusetts, meanwhile, have proposed legislation that specifically prohibits the use of deepfakes. Maryland plans to target deepfakes that may influence politics; Massachusetts wants to criminalise the use of deepfakes for already “criminal or tortious (wrongful) conduct”.

In 2020 California became the first US state to criminalise the use of deepfakes in political campaign promotion and advertising. The AB 730 bill makes it a crime to publish audio, imagery or a video that gives a false and damaging impression of a politician’s words or actions. Though the bill doesn’t explicitly mention deepfakes it is clear that AI-manufactured fakes are its primary concern.

In 2023, the governor of New York signed the Senate Bill 1042A. This aims to prohibit the dissemination of deepfakes in general, not just in relation to elections.

At least four federal deepfakes bills have been considered. These include the Identifying Outputs of Generative Adversarial Networks Act and the Deepfakes Accountability Act.

Protecting image rights

There is currently no recognition of image rights in South Africa’s case law or legislation. Image rights are distinct from copyright in law. The scope of protection provided by copyright alone would not be enough to tackle the problem of deepfakes in a court setting.

I argue for legal intervention which recognises individual image rights. By recognising an image right the image will be protected against unauthorised use. This will not only include the misappropriation of an individual image for commercial use, it will also combat deepfakes, whether those relate to elections and politicians or any manipulation of a person’s image with malicious intent.

Image rights legislation is key. It can:

- clearly define an individual’s image

- specify when an infringement of the image has occurred

- provide the image right holder with legal remedies for unauthorised use.

This can all help regulate deepfake situations. The malicious and deceptive nature of deepfakes may cause the image right holder to suffer significant harm. It is time that South Africa’s legislature addressed these situations by providing the necessary protection to individuals.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.